This post is old and has been updated!

Click here and read the new version instead.

To begin, *watch this quick video of an actual voltage drop test on a starter ground circuit by Peter Meier, technical editor for Motor Age Magazine (also a fan and supporter of AutoTechnician.org). Afterward, we’ll break it down in layman’s terms and figure out what’s going on here.

*May 2016 Update:

The original video that was on this post is no longer available so I will briefly recap what was in the video:

The original short video showed Peter demonstrating a Voltage Drop test on a vehicle’s ground cable circuit. The actual vehicle being tested by Peter was not experiencing any starting problems, however the voltage drop testing test he did can still be done regardless of the vehicle’s condition.

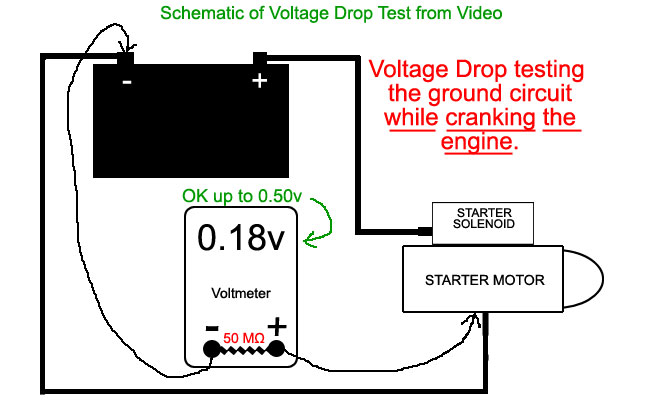

The test: With one voltmeter lead place on the negative battery post and the other is fastened cleanly to the engine block (also ground), Peter then watched the voltmeter screen while cranking the starter for a few seconds. The starter cranked over the engine normally and showed less than 0.21 volts on the voltmeter.

(This video below replacing the original one is a full in-depth tutorial on understanding and actually using voltage drop testing.)

https://youtu.be/n7-YSsWXVq8

Q: In this video the original video, Peter is testing the starter ground circuit with a voltmeter, but what is he actually looking for?

A: He’s looking for UNWANTED RESISTANCE in the active starter’s ground circuit but didn’t find any. Keep in mind, his demo vehicle doesn’t actually have a starting problem. But if it did have a problem in this car’s ground circuit, the voltmeter would have shown more than 0.5 volts while cranking.

It would be so much easier to understand if someone just labeled this test an “unwanted resistance finder” test. The term “voltage drop” throws off just about everyone.

Starting system resistance refresher: Unwanted resistance will cause a lack of current flow of electricity to and from the starter while cranking. If the starter didn’t crank normally, cranked too slow, or even not at all while attempting to do so, unwanted resistance could be the blame. Yes, the starter could be bad too, but we first have to eliminate every part of the starter circuit to be sure it is indeed the only problem. After all, the battery cables supply the starter. If they are “clogged” with too much resistance, electricity cannot “flow” as much as needed.

Now back to the diagnostic test: So before slapping on a remanufactured starter as many would do, Peter is testing and 100% eliminating the ground circuit from the starter ground (the engine block or transmission case) all the way back to the negative battery post – and in less than 2 minutes. Next, Peter would test the starter positive circuit the same way but connect the voltmeter between the battery positive post and the starter battery positive post and once again crank the engine and observe the voltmeter. So within about 4 minutes, Peter would know EXACTLY what was wrong with this starter circuit, or at least know where to begin looking further.

That’s the whole key – using a voltmeter to find resistance. One half of a volt is a general acceptable maximum limit voltage specification to go by on most vehicle starter/battery circuits. On some vehicles with more than one ground or positive cable in series, add another 0.5 volts for each cable to the total circuit.

Remember we need more voltage (or push) to overcome resistance. Electricity is always looking for an alternative path around any resistance it encounters. The voltmeter during this test will show you how much push, or voltage, the battery is using to try to bypass the resistance in the circuit you are testing. When the circuit you are testing is normal (very little to no resistance), the voltmeter will barely show an increase at all (less than 0.5 volts in general on a high load circuit like a starter).

Q: OK, why is a voltmeter used instead of an ohm meter?

A: An ohm meter uses it’s own internal battery to measure resistance, not the circuit’s power source. It is a good test for very small wires that require very small amperage to operate but NOT for thick battery cables! An ohm meter just doesn’t flow enough amperage to find resistance in large conductors. A known-bad battery cable can test perfectly good using an ohm meter but not be able to carry enough amperage to a starter while cranking.

More detail about ohm meters: An ohm meter flows very little current to find resistance – let’s say about 0.02 amps with a 9 volt battery compared to a 12 volt battery pushing 85 amps or more through a starter circuit. For an analogy, an ohm meter’s amperage moving through a battery cable is like driving one small car down a 85 lane empty highway. What are the chances of the ohm meter’s current hitting a traffic jam on a road that big? Not very good! Now compare that scenario to current flow in an actual starter circuit. It would be like driving 85 cars down that same 85 lane highway, all side-by side. One bad spot on this road will have a much higher impact on performance for sure.

So here’s the whole key to wrap up the voltage drop test: The circuit must be live. If there is any resistance at all between the two places your meter leads are connected to, resistance can be seen as an increase in voltage on the voltmeter display. Simply, the voltage on the meter rises when electricity encounters resistance somewhere between the two multimeter leads. Therefore it tries to bypass the resistance and try to go through the voltmeter instead. Now if we moved the leads closer together little-by-little, we can actually pinpoint the exact spot of resistance.

Need more theory to understand this? Then first learn how a voltmeter actually works: A digital voltmeter should have at least 35 million to 50 million ohms of internal resistance connecting the two multimeter leads inside it. An ohm is a measurement of resistance: more ohms = more resistance. Voltage is electrical “pressure” so a voltmeter measures the battery’s “pressure”. This “pressure” is used to push electricity (known as amperage, or “the doer”) from one side of the battery, through the starter, and back again to the other side of the battery. So think of a voltmeter as a PRESSURE GAUGE that measures the push needed to move electricity.

The numbers displayed on the voltmeter (or the PRESSURE GAUGE) show you how much potential pressure is in the circuit you’re testing.

NOTE: The circuit must be a live, active circuit for the voltmeter (or PRESSURE GAUGE) to measure anything during this test. It’s just like performing a fuel pressure test. The gauge would read zero pressure until the fuel pump runs.

A voltmeter in action: Connect a voltmeter across battery terminals to measure battery voltage. You’ve just created a live series circuit. A very, very, very tiny amount of current (about 0.00000002 amps) is now flowing through the voltmeter from one battery post to the other. The voltmeter display shows you how much pressure is in that voltmeter series circuit you just made. A fully charged battery of course would read about 12.6 volts (or 12.6 PSI if it was a pressure gauge). You are now looking at how much pressure is needed to push electrical current through the voltmeter’s 50 million ohm resister. This resistor is connected between the two voltmeter leads inside the meter. Seems ridiculous to have so much resistance, doesn’t it? It’s there by design.

Peter’s digital voltmeter has at least 50 million ohms of internal resistance built right into it on purpose. Why so much? Because that much resistance is needed to allow the voltmeter to sample the circuit you’re testing for available pressure without it interfering with or damaging the circuit you are testing. In other words, the voltmeter is used to “do a pressure test” without causing a change in the circuit’s voltage or current flow. If the voltmeter had very low resistance (just like older analog voltmeters or most test lights), electricity would now have an easier, optional path to go through. We don’t want to interfere with the circuit, we just want to look at it while it’s working.

Let’s look at our “voltmeter across the battery terminals” connection example again: The voltmeter (or PRESSURE GAUGE) reads 12.6 volts. As you may already know, electricity is always seeking the easiest path to from one side of the battery to the other. If there was an easier path while you were connected across the terminals, then the battery wouldn’t have to push so hard and the voltage (pressure) would be lower than 12.6 volts. But since there is not, the battery is pushing current as hard as it can through your voltmeter! Therefore it’s reading the full battery pressure (voltage).

Leave a Reply